|

|

|

|||||||||

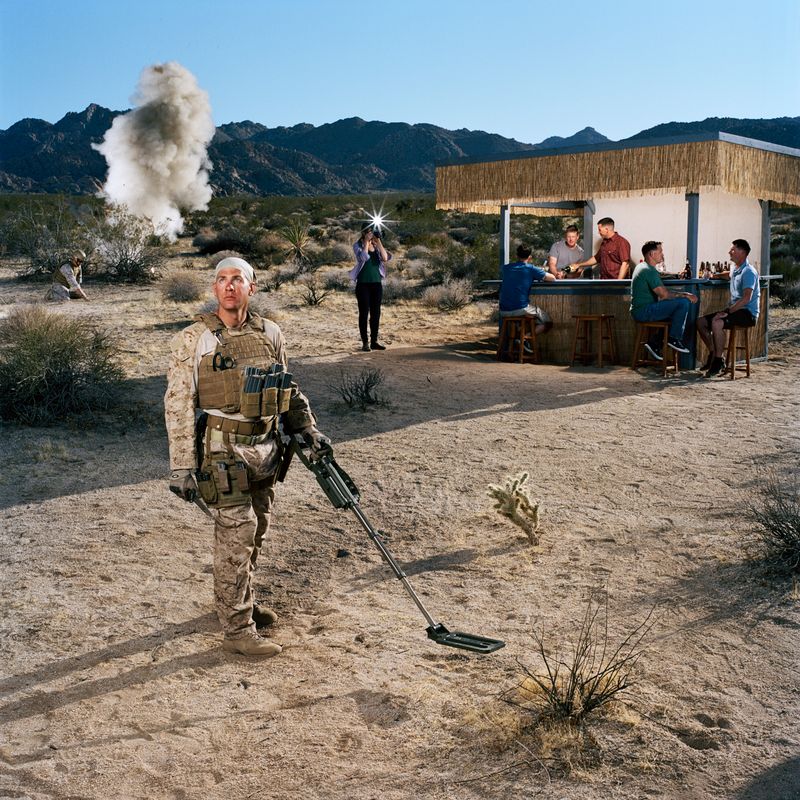

During my deployment in Afghanistan, we got information from one of our sources that there were improvised explosive devices [IED] set on a hilltop, so we went out looking for IEDs. We found two around eight o’clock that morning and set them off. We pretty much woke up the whole town because it was early. In our search, we went up the hill sweeping with our metal detectors. My team leader, Jeremy, was in a little low area between a couple of trees. I was watching him investigate an area—he was kneeling down probably within five meters from it when it went off. Time slowed down when I saw the explosion. I saw the fireball and the blast wave come out and push the trees and the dust and the dirt out and I also watched it suck itself back in, creating a mushroom cloud. I saw the fragmentation flying up in the air, and it was white and it was red and it was orange and it turned yellow. It goes up white-hot and as it’s coming down, it’s cooling down. I was watching it change colors. It was a very intense experience for a brief moment but it seemed like forever. I looked up and down at both of my arms and thought, “OK, I don’t see any holes, I don’t see any blood, I feel OK.” I looked at my legs and did the same thing. Then I started getting up and yelled for Jeremy to make sure that he was OK. I heard him and I knew that he was at least coherent. Our third team member, Matt, was on the other side of the hill and he was OK too. We all regrouped in our little safe area. My right ear was ringing, as was everybody else’s. We calmed ourselves a little bit, we all smoked cigarettes. We replaced the batteries on our counter-measures equipment and we went back in. We had to do an investigation. I was scared shitless going back again. I was thinking, “What the fuck!?” My whole body was shaking as I was sweeping. But I kept calm enough to know, “This is part of the job. This is what we’re doing. And this one’s already gone off so it can’t be too bad.” It was almost a year later—I was out in a bar with a bunch of my friends. People were taking pictures and one photograph flash caught my eye in the same manner that that IED had gone off. And I lost it. I was freaking out. I was wondering where my friends were. “Where am I? What am I doing? Is everybody OK?” I walked around the bar searching for my friends and picking them out. “OK, there’s my friend—he’s safe. There’s my friend—he’s safe. There’s my friend—he’s safe. There’s his girlfriend—she’s safe.” I knew physically I was still in a bar but mentally and emotionally, I was back in Afghanistan. I saw the camera flash and my brain instantly saw that explosion flash, and it went back to seeing everything. After that, I talked with my friend because he’s been in some past experiences and he suggested that I go to see his therapist. I went the very next day. I’m glad that I did because the therapist I saw really helped me. That’s the only experience I’ve had with more or less being blown up so far. I hope it doesn’t happen again, but I’m still on the job. I mean, there’s still always the potential and possibility whether we have to go back to Iraq or Afghanistan or wherever else in the world. Kyle Winjum is an active duty Marine who was stationed at Twentynine Palms Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center when Jennifer Karady met him. He is currently stationed at Camp Pendleton in a deployable unit. This text was transcribed and edited from interviews conducted by Jennifer Karady in March 2014. This text was transcribed and edited from interviews conducted by Jennifer Karady in April and May 2011. |

|||||||||||

© Jennifer Karady 2022, all rights reserved. |